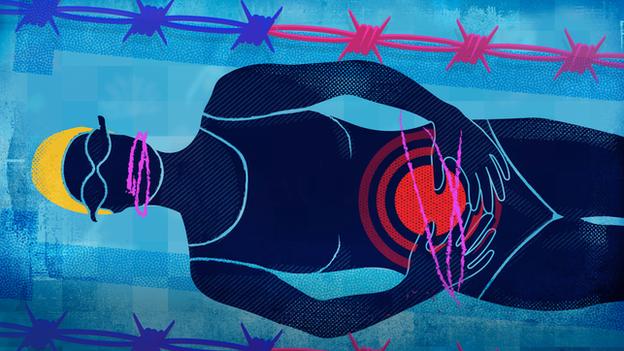

International Women’s Day: Understanding endometriosis in sport

No-one knows your body better than you. You’re the one who feels every ache, pain, and scratch. You’re the one who knows when something is wrong.

But what if everyone else – doctors, coaches, relatives – tell you there’s nothing to worry about, that it’s all in your head? It can leave you wondering if you’re “crazy”.

Endometriosis affects one in 10 women. It takes, on average, seven and a half years to be diagnosed. It has a powerful effect on every part of a woman’s body. For an athlete, it can be the difference between being selected or being seen as a liability. Between staying in your profession or losing your sponsorship. Between being in a clear headspace or doubting your every ability.

Pain. Cramps. Blood. Then surgery. Incisions. A camera. A chemically induced menopause. All these things – inconveniences, intrusions, life-altering changes – to finally be told that no, you’re not imagining it; no, we can’t cure it; yes, we probably could have caught it sooner.

Endometriosis is not spoken about enough. It’s not well enough understood. It’s time it was.

When you break it down, endometriosis sounds quite simple – a condition in which cells like the ones in the lining of the womb grow elsewhere in the body.

It hurts. It really hurts. Most women are conditioned to expect pain during their period, which partly explains why diagnosis is so difficult. Some women might dismiss the symptoms, and see it as something they just have to get used to. Take a few painkillers and get on with their day.

Even when the pain is clearly more serious, it often takes repeated visits to a doctor, with the patient having to insist something is not right, before the first steps are taken towards a diagnosis. A diagnosis. Not a cure.

Elinor Barker describes feeling as though someone was ringing out her organs as if they were a tea towel. Kirstie James was in so much pain that, as she fell to her knees on her kitchen floor, she thought she had torn a hip muscle. Monique Murphy knows pain; she had to rebuild her life after falling from a fifth-floor balcony and losing her right leg. But the electric shocks running up her leg and the cramping were something entirely different.

These three women are Olympic, Paralympic and Commonwealth medallists. They have represented Great Britain, New Zealand and Australia respectively, while dealing with endometriosis. All three say they thought they were going crazy as they were told there was nothing wrong with them. Multiple doctor visits, competitions missed, being unable to move as their muscles seized. It’s a common thread throughout their stories.

“Between my first doctor’s appointment and actually having surgery I went to four World Championships, the Olympics, the Commonwealth Games and loads of events,” British track cyclist Barker says. “Within six months of my operation, it was agony. The pain would be there for weeks on end and then it would disappear.

“The fatigue was a real killer. I was exhausted all the time from having to deal with this pain. It was keeping me up at night, stopping my training sessions, stopping me from wanting to go out because I just wanted to be curled up in a ball all the time. At its worst, it would control my whole day.”

Barker found she was in pain up to three and a half weeks each month. Her coaches and team-mates were aware she was struggling, but she worried she would be seen as a risky option in team events.

After four years, and five or six male doctors, Barker met a female doctor shortly before the 2018 Track Cycling World Championships. She was finally diagnosed with endometriosis. As the only treatment was surgery, she opted to wait until after the competition.

“I felt like I really scraped through and had to put on a brave face,” she says. “I pulled out of the madison as a result.

“I think at the time I said I’d hurt myself badly in a crash in the omnium. It seemed a more legitimate reason. I had hurt myself but the underlying issue was I didn’t feel up to it because of the pain I was in. The crash seemed a more legitimate reason. When you’re surrounded by men, you have to give the reasons that fit.”

Fellow cyclist James was told that she couldn’t be counted on because of the inconsistencies in her performance. She knew there was something wrong.

“I couldn’t figure out why I was having these extreme swings between really good form and then struggling to get through a normal session,” she says. “I talked to my sports doctor, and during a routine exam she pressed down on my belly.

“One place where she pushed was really sore, towards my right hip flexors, it was so painful. I didn’t think too much of it again until one day I was cooking dinner and I felt this extreme pain in the same place. I was in absolute agony.”

James was referred to a gynaecologist. After telling him about her family history – her mum had endometriosis and adenomyosis (irregular cells embedded in womb) – she was booked in for surgery. They found a fallopian cyst “the size of a golf ball” that was bulging outwards. The cyst would tangle, cutting off the blood supply, and causing stabbing pains in James’ hips.

This was in 2016. James researched the surgery. A small cut would be made in her stomach and a camera would be inserted. If they found no endometrial tissue, the surgery would end. However, if they did, three, centimetre-long incisions would be made further down the body, allowing the endometrial tissue to be sliced out.

“I remember waking up and thinking, ‘I really hope they’ve found something because then I’m not crazy,'” she says. “I remember scrambling the hospital gown to try and see how many cuts there were on my belly. When I saw four of them I felt this huge weight off my shoulders. It’s like, ‘I’m not crazy; they did find something and I’m going to get better.'”

Swimmer Murphy was flying to the biggest tournament of her career, the 2016 Paralympics, when she got her first period for two years. She now recognises this as her first real flare-up of endometriosis – “I was so sick, in so much pain and flooded with fatigue” – and she went to her team doctor.

She feared she had food poisoning, with her heart rate more than 200 beats per minute when she warmed up in training. She says: “I told the doctor I wasn’t feeling good and she goes: ‘Oh, that’s fantastic, that means your body is healing from the accident you had falling off the balcony.’ She walked off and that was the end of the conversation.”

Her period lasted for two weeks, stopping just before her event, in which she won silver. But her struggle for recognition – for people to believe there was something wrong that needed treatment – continued.

There is now a wider understanding than ever of how periods affect athletic performance – but not so long ago the entire subject was brushed aside. Understanding why helps explain sport’s lack of awareness surrounding endometriosis.

“Some of the conversations I would have with coaches would be, ‘Oh, we always know when such-and-such is having a period because we all put our hard hats on,'” says Dr Anita Biswas, the co-lead for female athlete health and performance at the English Institute of Sport (EIS).

“It’s that kind of thinking that women go a bit mad when they’re pre-menstrual. Well, do you talk to them? Do you ask them how they’re feeling and how it is impacting them?

“If you’re that athlete, who feels so emotionally in a mess, you’re trying to perform at your best, and everyone is kind of turning their back on you because they don’t know how to talk to you, that’s going to make you feel even worse.”

Google ‘period symptoms’ and you get the list that most women have memorised since they were first introduced to a tampon. Bloating, cramps, fatigue, bowel problems.

Now say you’re an athlete. Your job is to run, or swim, or cycle. That’s how you sustain yourself; how you define yourself in some cases. And it’s quite possible that your funding depends on how many medals you win, or how well you perform at that week’s competitions. When endometriosis, a condition that causes severe cramps, back pain, nausea and heavy periods, enters the frame, that performance is inhibited.

For a Para-athlete such as Murphy, performance dips threatened her funding. Losing that support would have a huge impact on her life and career. So she made a decision.

After consultations with 14 doctors, she had surgery and was diagnosed with endometriosis, alongside adenomyosis. At 26, she decided to go through a chemical menopause; a temporary menopausal state which suppresses hormones and stops periods. That in itself brings its own problems – Murphy has hot flushes and joint pains – but for her, it is better than the pain and “brain fog” she experienced before.

More women than ever are speaking about their experiences of endometriosis. BBC broadcaster Emma Barnett’s book focuses on her understanding of the condition and her body, while MPs in the UK have recognised the need to improve the care women receive and cut diagnosis times.

“Probably the hardest part about this was the mental side and not being believed,” Murphy says. “I didn’t want to use the excuse that I don’t feel well, especially when I don’t know what’s going on. Maybe my body is OK, maybe I’m just not strong enough. Maybe this is what hard work feels like and I don’t have what it takes.

“It’s a mental back and forth that was probably the hardest. Not having a leg is a very visual impairment. People see it. You get sympathy, you get pity, you get every emotion that you don’t even want from people. But this is different.”

Attitudes need to change – and they are. James says her pain has decreased by 95% since her surgery, while Barker says she and her international team-mates are happy to be open and discuss their menstrual cycles and problems with coaches and one another. The medical and scientific community within sport does more research than ever into periods, and the EIS educates coaches and athletes on understanding these issues.

It is talking – discussing, laughing, crying, sharing, understanding – that will create more understanding and force these issues to be taken increasingly seriously.

Murphy has had no more endometrial growth since her surgery and jokes she and a few other swimmers are in a ‘menopause club’, after it was decided that was the best course of treatment for her adenomyosis.

As she puts it: “The joys of being a woman? Mate, you’ve got no idea.”

March is Endometriosis Awareness Month across the UK.

Culled from BBC

Comments are closed.