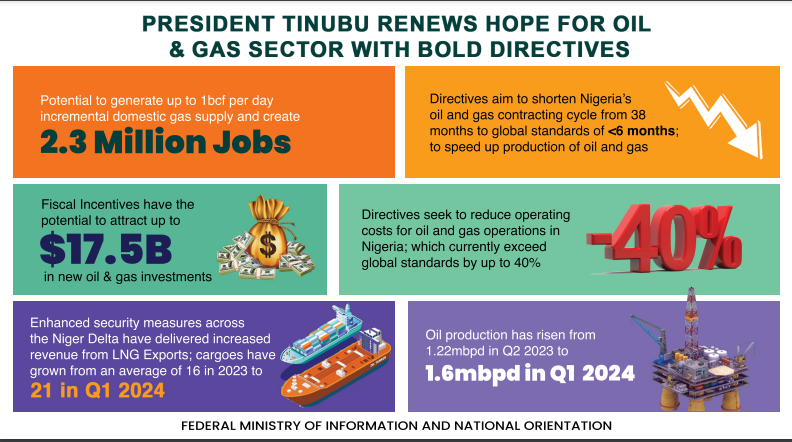

Why Africa Is Poised To Become A Big Player In Energy Markets

Energy markets are being rocked by an unprecedented double-whammy. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year, Europe has cut energy imports from Russia, the world’s second-largest producer of natural gas and third-largest oil producer. Prices of both shot up before falling back, but anxiety persists about energy security. Meanwhile, climate change is prompting a deep but uncertain shift away from fossil fuels such as oil and, eventually, gas. Europe’s politicians and industrialists worry about keeping factories humming and homes warm in the face of these challenges.

Africa may be the answer to Europe’s immediate gas problem and its longer-term carbon one. It has 13% of global gas reserves, only a touch less than the Middle East, and 7% of the world’s oil as well as vast green-energy potential. African energy could “become really central for the future for Europe—and not just for Europe,” says Claudio Descalzi, the CEO of Eni, the Italian oil major. “They have a lot—a lot—of gas, they have sun, wind…[that is] perfect for our energy transition.”

This talk is not hot air. International energy firms including Eni are dusting off or drawing up new plans to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG) across the continent. Among these are moves to restart two huge LNG projects that had been shelved, including a $30bn-40bn one in Tanzania and another worth $20bn in Mozambique.

The activity marks a sharp change in the prevailing mood over the past few decades, when Africa had dwindled in importance to energy markets. A continent that once provided a fifth of the world’s internationally traded lng now provides half that share. Its shares of global oil and coal production have also fallen as investors in oil, in particular, have been put off by deteriorating security in Nigeria, usually the continent’s biggest producer.

Higher prices, increased European demand as the eu diversifies away from Russia and a switch from coal to gas, a cleaner fuel, are driving the change. And the swing is swift. Mozambique shipped its first lng in November and may soon export vastly more. TotalEnergies, a French oil major, could soon restart building a giant lng project in Mozambique that it halted in 2021 because of a jihadist insurgency. Patrick Pouyanné, the ceo of TotalEnergies, tells The Economist that the project is almost back on track and so should be producing gas by 2028. Improved security could also boost the prospects of an even larger lng project nearby that is proposed by Exxon Mobil, the largest Western oil major, and China National Petroleum Corporation. Across the nearby border in Tanzania, Shell and Equinor, two European energy companies, are resuscitating their proposed $30bn-40bn lng project.

Elsewhere, an lng project in Senegal and Mauritania is expected to start producing this year and the prospects of its second phase look promising. In Nigeria, Africa’s biggest lng exporter, production capacity should rise by about 35% by 2026.

In all, new gas projects in sub-Saharan Africa could add some 90 billion cubic metres (bcm) in annual lng capacity by 2030, reckons Akos Losz of Columbia University. To be sure, only about a fifth of this capacity is already under construction or not on hold for security reasons and some projects may yet fail. Yet energy firms seem determined to press ahead. New projects in north Africa, where Eni just signed an $8bn deal to develop two Libyan fields, could supply an additional 30 bcm of gas by 2030, reckons Mr Losz. Rystad Energy, a research firm, sees similar potential (see chart). If all go ahead, the 120 bcm added to Africa’s current output would raise its share of global gas production to 8.5%, from 6% today, even taking into account massive increases expected in Qatar. The additional production expected in Africa alone would more than offset the 70 bcm fall in Russian gas exports to the eu between 2021 and 2022.

Over the longer run Africa seems set to play an even bigger role in energy markets. The Gas Exporting Countries Forum, a global club of gas-exporting countries, expects Africa to add more gas capacity than any other region bar the Middle East. It reckons Africa will be producing almost 600 bcm a year by 2050, up from 249 bcm now.

Counting rigs, not rigging counts

Other indicators seem to support these bullish forecasts. The number of rigs operating in Africa, a leading indicator of exploration and production, is at is its highest since 2019, according to Rystad. Spending on African exploration and development is expected to reach $46bn this year, the highest since 2017. Meanwhile Africa’s share of global capital expenditure on gas has more than doubled since 2014, according to Wood Mackenzie, another energy research firm.

Oil is also attracting investment. TotalEnergies, the world’s third largest international oil and gas firm, will spend half of its global exploration budget this year in Namibia, where it appears there may be as much as 11bn barrels of oil and potentially gas too. That could make Namibia a huge producer. “We have no doubt that it’s going to happen,” says Namibia’s energy minister, Tom Alweendo. Even modest hydrocarbon exports can have a big impact on poor countries. Take Niger, where a Chinese-built export pipeline is nearing completion. “Next year alone it will bring budget resources worth a quarter of our current budget,” says Mohamed Bazoum, the president of Niger. “The following years it will be even bigger.”

Africa also has vast potential to be a big producer of green energy. Although it has sunny, spacious deserts, windy coasts and plains and gushing rivers, it has been a laggard and has just 1% of the world’s installed solar and wind capacity and only 4% of hydropower. This, too, is changing, though perhaps not quickly enough: installed solar capacity in Africa has almost quadrupled since 2016.

Africa has punched below its weight mainly because it has been hard to export green energy. Investments were made mainly for local consumption of electricity (which is less than 3% of the world’s total) and even privately owned power producers often struggled to make money because they supplied small markets through inefficient state-owned utilities.

Now new technologies could allow renewable-energy producers to sidestep problems in domestic markets by exporting energy. With assured revenues from exports, green-energy firms can more easily secure the investment needed to build big and efficient plants. One spillover is that they should then also be able to provide power to local economies.

The first of these export opportunities is through producing so-called “green hydrogen”, which is made by splitting water into oxygen and hydrogen using renewable electricity. Rich countries see green hydrogen as the best hope to keep their energy-intensive industry running while slashing carbon emissions. America recently introduced the largest subsidies in the world for low-carbon hydrogen (which includes that produced with gas and carbon capture). The EU’s new energy programme, designed to make the bloc independent of Russian fossil fuels, has set a target for Europe to produce 10m tonnes of green hydrogen a year and to import 10m tonnes more by 2030. The IEA, an intergovernmental think-tank, reckons the world will need to produce 90m tonnes of low-carbon hydrogen a year by 2030 and 450m tonnes a year by 2050 if it is to reach its goal of net zero emissions by mid-century.

Africa’s strong solar and wind potential makes it an attractive place to produce green hydrogen. A recent study by the European Investment Bank (EIB), the EU’s development bank, argues that Africa could produce 50m tonnes of the stuff a year by 2035 from three subregions: Egypt; Mauritania and Morocco; and Namibia and South Africa. About half of this could be for export. “Namibia has the potential to become one of the main renewable energy hubs on the African continent and worldwide,” gushed Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, in May. The bank reckons Mauritania and Morocco could be one of the world’s most competitive producers, with costs including transport to Gibraltar of about $1.6 per kg by 2035.

Gas in the tank

Big hydrogen projects are starting to gather speed in Africa. One of the largest is in Mauritania, where last year the government and cwp Global, a green-energy company, signed an early agreement for a wind and solar project to produce 1.7m tonnes of green hydrogen a year. Another megaproject in Mauritania by Chariot, a British firm, and a subsidiary of TotalEnergies, aims to produce 1.2m tonnes a year. “This is an extraordinary opportunity,” says Abdessalam Ould Mohamed Saleh, Mauritania’s energy minister.

The excitement is similar in Namibia where the government recently finished negotiations with Hyphen Hydrogen Energy, a renewable-power firm, for the next phase of a $10bn project that aims to produce 2m tonnes a year of green ammonia (a product made from green hydrogen that is transported more easily) by 2030. It is backed by the eu. “They need the molecules. We need the jobs,” quips James Mnyupe, an adviser to Namibia’s president.

Green hydrogen is not the only possibility for exporting renewable energy. Xlinks, a British firm, is planning a wind and solar plant in Morocco that would send electricity directly to Britain along 3,800 kilometres of deep-sea cables by 2030. The project could provide 8% of Britain’s electricity at a much lower cost than alternatives such as a long-delayed nuclear power plant, says Xlinks. Though its $18bn cost is a considerable hurdle, the project has attracted initial funding from Abu Dhabi’s national energy company.

For Africa to realise its energy potential it will need to dodge a series of pitfalls. The first danger is sloth. On natural gas, competitors such as Qatar and America are moving quickly to expand their production. If Africa is tardy its window of opportunity to supply Europe may close, particularly as demand shifts to greener sources of energy. The iea reckons that by 2030 the eu may use 20% less gas than it did in 2021 based on current policies.

Africa’s record on speed is worrying. Over the past two decades, new gas projects in sub-Saharan Africa have taken almost 5 years longer than expected to go from discovery to production. On the other hand, African oil and gas producers are reasonably cost-competitive, meaning they will not be the first to struggle if falling demand hits prices. At a gas price of just $3 per 1,000 cubic feet, two-thirds of African gas is still profitable. This includes much of the gas found in Algeria, Mauritania, and Tanzania (see chart). Even in oil, which is dominated by low-cost Saudi production, Africa is still largely in the game at prices above $30 a barrel.

Meanwhile demand for gas is expected to grow in Africa itself as the continent moves to produce electricity for the roughly 600m Africans who do not currently have it. Much of this new supply will probably come from renewable sources, but gas could also be an important part of a stable electricity mix and also fire the furnaces of heavy industry.

Firms and governments are also working to ensure that Africa’s natural gas is extracted in the most climate-friendly ways possible. Eni claims that its development and operation of the Baleine oil and gasfield in Ivory Coast will be the first in Africa to have net zero emissions (though that does not count the emissions from whoever buys and burns the oil and gas).

The second major pitfall threatening Africa’s energy boom is domestic security. Jihadists have already delayed the construction of Mozambique’s mega gas projects by several years and prompted the country’s neighbours to send in troops to restore order. Meanwhile, Nigeria partly missed out on the windfall of high gas prices last year as a lack of security led to it shipping less lng in 2022 than the year before.

The third hazard is disputes over how the rents from energy production are divided. The dollars big oil and gas projects earn could be grabbed by well-connected politicians and businesspeople, rather than benefiting the population as a whole.

Alas governments in the region do not always have a good record of productively investing revenues from resources into infrastructure, schools, and clinics. In Equatorial Guinea, for example, oil has propped up the world’s longest-ruling dictator. His playboy son, who hopes to take over, is known for splashing the cash on mansions and fast cars (and squandering the rest). Meanwhile the people of Equatorial Guinea suffer. The country ranks 145 out of 189 on the un’s Human Development Index, a measure of income, health and education.

Shakedowns of oil and gas companies and nationalisations of their assets are still worryingly common in Africa. In Ghana, usually one of Africa’s better investment destinations, Tullow Oil is going to international arbitration after being given a retrospective tax bill of $387m as the country scrambles for funds amid a public debt crisis. Investors considering pumping in the billions of dollars needed to produce lng or green hydrogen will not do so if they fear their assets will not be safe, or if the rules will be arbitrarily changed.

This is especially the case for green hydrogen projects, which will need to attract formidable amounts of capital. Namibia’s proposed project will cost about $10bn; not much less than its current GDP of $12bn. The estimated investment needed for the eib’s pan-African vision to produce 50m tonnes of green hydrogen per year by 2035, including everything from solar installations to export pipelines, is $1.4trn. The biggest problem is whether companies and governments in the rich world, who want green hydrogen, will invest. “Will words become deeds that meet needs?” asks NJ Ayuk of the African Energy Chamber, an industry body.

After decades of declining relevance to global energy markets, Africa has a brief moment of enormous opportunity. To seize it, Africa’s governments will have to learn from the mistakes made in previous commodity booms, when investors were frightened off and revenues were squandered. Adonis Pouroulis, the ceo of Chariot, believes that this time the continent will not waste the opportunity. “This century,” he says, “is Africa’s century.”

Comments are closed.