Crime Is Engulfing Abuja, And Authorities Are Blaming Rickshaws

At the Gudu junction where the expansive main road of Abuja’s business district ends, dozens of yellow three-wheeled rickshaws have commandeered a portion of the highway, jostling to pick up commuters heading into the suburbs at the close of work.

But Nigeria’s capital plans to ban an essential mode of transport for its millions of poor citizens because of the role authorities say they play in a crime and kidnapping crisis that is engulfing the country’s second-richest city.

“It is painful, but it’s an inconvenience that we must face,” Federal Capital Territory Minister Nyesom Wike told residents’ associations in a November meeting. “Some of these keke Napep are agents of criminals.”

With its tree-lined boulevards and picturesque hill outcroppings, Abuja is touted as Africa’s model capital by Nigeria’s ultra-rich politicians, its high rents acting as buffer against the poor. But growing poverty and insecurity have driven a large number of poor people into the city, leading to the rise of urban slums, symbolized by the rickshaws.

“We must bring the FCT back where it is supposed to be,” Wike said on his first day in office as territory minister in August. By targeting the rickshaws, he’s seen as executing an elitist agenda of reclaiming Abuja for Nigeria’s rich.

Removing the keke Napep — the former being Yoruba for bicycle and latter a reference to a 2001 national poverty-eradication program that drew thousands of people to Abuja to eke out a living by driving the three-wheelers — risks leaving commuters stranded, because the capital hasn’t provided public-transport alternatives.

It would also put thousands of drivers out of work in a country with the largest population of poor people after India and where millions are underemployed.

Anyone that has seen the rickety tricycles — with a maximum speed of about 70 kilometers (43 miles) an hour at best — struggling to climb one of the city’s many hills will question how they can be getaway vehicles for criminals undertaking targeted robberies known as one-chance.

The drivers say the government has unduly targeted them as it seeks an easy way out of its inability to secure the capital — a solution that singles out the poorest.

“Keke that can’t run, keke that can’t fly — how can keke do one-chance?” asked driver Kabiru Isah. “They should say rich people don’t want poor-man keke to be near them.”

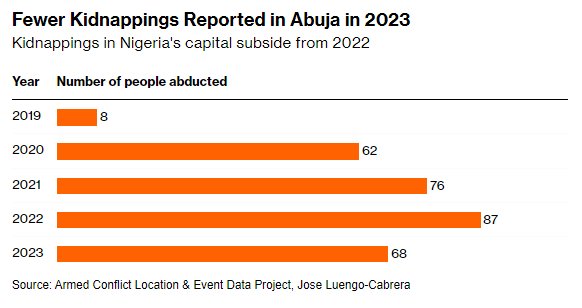

Since the mid-2000s, Nigeria has been at the mercy of kidnap-for-ransom gangs that target both the rich and poor for payments as low as 20,000 naira ($14).

The abduction of 12 people from two families on the outskirts of Abuja in early January was a stark reminder of the criminals’ brazenness: They murdered a 21-year-old woman and 13-year-old boy from each family, making good on their threats after relatives didn’t pay a 100 million-naira ransom. The remaining family members were released on the night of Jan. 20 in a forest in nearby Kaduna state.

Residents are enraged by the police’s inability to protect them, and by city management’s failure to maintain roads and streetlights, creating fertile conditions for carjackings and kidnappings at busy junctions.

Abuja has missed its own December deadline to take kekes out of circulation. And while city management plans to switch to gas-powered buses, not a single one of those vehicles is on the road.

Many of Abuja’s keke drivers are from northern Nigeria, ravaged by more than a decade of conflict by Boko Haram Islamist militants and more-recent activities by armed gangs called bandits. Many of them were farmers who — deprived of their livelihoods — headed to the capital seeking to make a living. Now, the city wants to push them out.

They will be pushed into the “rural areas,” said Wike, who built his reputation as a hard-man governor who resuscitated the southern oil city of Port Harcourt. He has vowed to restore the capital — constructed from scratch in the 1980s when the national government moved from Lagos — to its past glory.

Wike’s office declined to provide more information on the exact date and which areas of the capital the kekes will be confined to.

“Every business has bad people. Most times the thieves steal the kekes and use it to carry out the attacks,” said Mansur Musa, secretary of the tricycle riders’ association in the Kabusa suburb, where the roads are narrower and the government has never installed traffic lights.

Many of the drivers — who include university graduates unable to find work — bought their kekes through hire-purchase arrangements, hoping to repay them in under two years by giving 30,000 naira weekly to their benefactors who purchase the vehicles for as much as 3 million naira. A few of the drivers received the vehicles during electioneering campaigns, when the tricycles are choice items for politicians seeking to gain votes.

It’s hard to know the accurate number of kekes in Nigeria — various estimates say hundreds of thousands — but as they’ve increased in affluent cities such as Lagos, Kano, Port Harcourt and Abuja, so have the clashes with motorists and pedestrians.

“They might be slow, but the thieves among them carry weapons with which they coerce victims,” said Biola Ahmed, an Uber driver who has lost count of side-mirrors damaged by tricycles.

There are no training schools to learn how to ride a tricycle; it is left to friends and neighbors to show newbies the gears. The operators aren’t licensed, unlike car drivers who need to show that they understand road regulations, and when there are accidents with other vehicles, keke drivers have sometimes banded into violent mobs.

“They don’t obey the traffic rules: When the light says red, they think that it is meant for cars and it doesn’t affect them — some of them drive against traffic,” said Reynolds Shodeinde of the Institute of Chartered Transporters and Logistics Operators. “But you cannot take them out completely, because where is the alternative for last-mile transport?”

A batch of privately donated buses are awaiting a ribbon-cutting ceremony close to the presidential villa, while most of the diesel buses of the old mass-transit service are parked in a garage on the outskirts of the city.

“I assure you that once the buses and taxis are on the roads, the problem of one-chance will be a thing of the past,” Wike said. “However, if you make the mistake of going to enter a taxi and a bus that is not our own, it is your problem.”

Comments are closed.