Whereabouts Of Tola Wewe’s ‘Iye Boabo’ And the present day value

While the Nigerian security agents care little about recovering stolen artwork, a job they could often better be equipped to perform than aligning with bus conductors at bus-stops, it appears art and antiquity crime is tolerated, in part, because it is considered a victimless crime.

But in an ode to human creativity that sounds a little odd coming from our environment, art thieves steal more than beautiful objects; in the works of art they steal memories and identity. They steal history, economic and monetary value.

Yes, the value as represented by John Maynard Keynes, the famed economist, who said: “In the long run we are all dead.” That was in response to the equanimity some economists expressed in the face of short-term crises.

Keynes was more than an economist, though. He was an investor and, it turns out, an art collector. Jason Zweig, the Wall Street Journal’s investing columnist, wrote about an academic paper on Keynes’s art collection some time ago.

Like most collections, the lasting monetary value of Keynes’ collection included works by Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat and Pablo Picasso. “Of the 135 works in Keynes’s collection,” Zweig says, “two account for more than half its total value and 10 constitute 91 percent.”

As the value of art increases in commercial and critical appreciation, then the bad and the good news in Nigeria. The Nigerian secondary market appears to have uncovered a painting placed on ‘stolen’ list for 29 years. Yes, ‘stolen list,’ perhaps not an instance to create fake ownership history and peddle the valuable to any collector in the world.

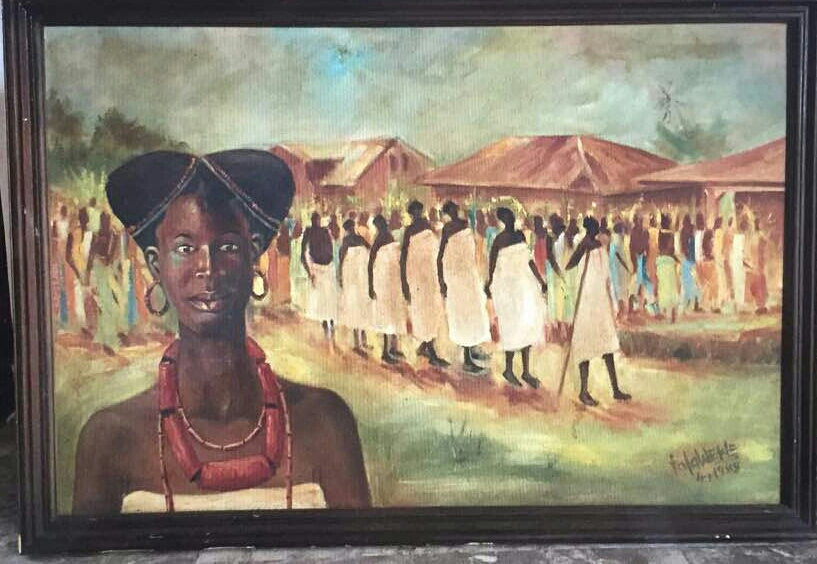

Titled ‘Iye Boabo’, by Tola Wewe, the painting, according to the artist, was exposed by Nigeria’s leading auctioneer, Arthouse Contemporary, during the preparation for another sales scheduled for this month of May, 2018. ‘Boabo,’ after which the artwork is titled, is an annual cleansing festival at Igbobini, an Apoi-Ijo community in Ese Odo Local Government Area of Ondo State.

However, the unearthing of the painting may also give a lead to the others with over 100 artworks allegedly stolen at the same time ‘Iye Boabo’ was declared missing. In fact, Wewe had told select guests in Lagos a few weeks ago that the store in which the works were kept was looted then.

In 1989, Wewe, Moyo Okediji, Kunle Filani, Tunde Nasiru and Bolaji Campbell – all founding members of Ona – had a group art exhibition at University of Ibadan, Oyo State to mark the arrival of the movement.

After the exhibition, the works of the Ona artists, according to Wewe, were kept inside Okediji’s apartment at Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. However, Wewe claimed that he didn’t know the works were looted until many years later. He recalled going to Fenchurch Gallery, Onikan in 1996 and saw one of Okediji’s works.

Wewe attended University of Ife in 1983, where he bagged a degree in Fine Art. In 1986, he went further to obtain a Masters degree in African Visual Arts from the University of Ibadan, Oyo State.

His works have three major influences which are; his academic training at Ife, his Ijaw water spirit mask masters research programme and the Yoruba society in particular. All these were what influenced his early works.

Communicating his finding to Okediji from Nigeria then, he said, was difficult until many years later when the two artists reconnected in the country. “It was then Moyo told me that those paintings, including mine, were stolen.”

Strangely, the artists did nothing about revisiting the stolen works, even the one seen at Fenchurch. A few weeks ago, the incident of the ‘looted’ works was revisited elsewhere: Arthouse got in touch with Wewe over ‘Iye Boabo’ asking the artist to confirm the provenance of a work that the auction house said was submitted for auction.

With the controversy surrounding the appearance of the artwork at the next Arthouse’s auction, Wewe was not happy that the identity of the collector of the work remained elusive and unknown to him a week after he and Arthouse had conversations. But Arthouse insisted that the holder of the work was disclosed to Wewe during a phone conversation.

After the exchange of numerous emails, Wewe and Nana Sonoiki, Arthouse’s expert, extended the conversation to WhatsApp, a social media platform, over the provenance of the controversial painting. It runs thus:

Wewe: “It is one of my missing works. I will give the title, stories about the work, etc. But I must earn my remuneration”.

Nana: “Thank you!”

Two days later. Wewe: “Still waiting for your response on the work

Nana: “I forwarded your mail to the owner and no response yet”.

Wewe: “We need to act quickly because I may be forced to make this public o”.

Nana: How? That we stole your work?

Wewe: Arthouse has no problem”. The artist later added. “Infact you are my saviour now. If not for an institution like Arthouse, how would I have seen this work?”

The same day, Wewe made a request: “Kindly tell him to link up with me so that we resolve the issue or I go through my own way”.

Earlier in the initial mails exchanges, Sonoiki wrote: “The attached work has been submitted for our coming auction, we Kindly request your assistance with the following information;

Title, medium, artist’s statement.

“We look forward to hearing from you”, Arthouse’s expert, Nana Sonoiki mailed Wewe on April 18, 2018.

“The painting is mine. I have the title and the story that inspired the painting. I am very pleased to discover that this painting is still living because I have been looking for it since the late eighties.

“I would be glad to know who the collector is and probably agree on some terms before giving you further details on the work,” Wewe replied.

In a few hours, Sonoiki denied shielding the identity of the collector from Wewe. She expressed disappointment in Wewe and condemned his hasty run to the public. She confirmed the conversation between her and Wewe, but that the reason she did not get back to him for almost 10 days was because “the client” who submitted the work had taken ill and so could not read the mail she had sent to him. She, thereafter, divulged the name of “the client” as Mr Mike Oduah.

For almost three decades of keeping the artwork, it is expected that whoever has been with it should be willing to pay the value based on appraisal, considering the worth as an average return even when adjusted for inflation and any other considerable economic factor.

Comments are closed.